- Home

- Tony Parsons

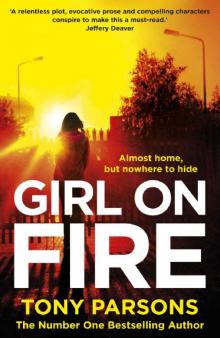

Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe Page 5

Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe Read online

Page 5

He did it gently at first, finding his range, and then he did it much harder. And then he did it harder still, twice, the kicks coming so close together that the sound of his instep repeatedly striking the bag seemed to become one unbroken sound, like hailstones. Then he stood back, bouncing up and down on the soles of his feet, his hands loose at his side, a thin film of sweat on his face.

Fred and I were grinning at him.

‘Oy, Conor McGregor,’ Fred said. ‘You training or dancing?’

Jackson showed us his gap-tooth grin.

‘Got some spare kit?’ he said.

So Jackson and I trained together on one of Fred’s famous circuits. A dozen three-minute rounds on the speed ball, the uppercut bag, the heavy bag and the super heavyweight bag, that long two-metre slab of hard leather that drained every ounce of energy out of you, a one-minute break between rounds filled with ten burpies and ten press-ups. Forty-eight minutes with no breaks. Recover while you work.

‘You’ll sleep well tonight,’ Fred said as the final buzzer went after the last press-up, when we were on our hands and knees and the tank was empty for both of us. Jackson smiled at me and I saw that he was full of that exhausted happiness that only comes on the far side of hard exercise.

After we were showered and dressed, Jackson said we should get a beer in one of the many pubs around Smithfield that cater to all manner of night owls, including the club kids at Fabric on Charterhouse Street and the night shifters from the meat market that has stood on this spot for a thousand years.

He could tell I was not keen.

‘I know you want to get back to Scout. But have just one beer, Max. It’s been a long day for all of us.’

I waited for the real reason.

‘We need to get our story straight,’ he said.

We sat at a corner table of one of those legendary Smithfield boozers that roar while the city sleeps, and we were the only men in there who were not wearing white coats, the only men in there who were not splattered with blood. I watched Jackson sip his San Pellegrino. It took some nerve ordering a sparkling mineral water in here, but Jackson Rose had never lacked nerve.

‘Are you in trouble, Jackson?’

‘Me? Trouble? No. I’m suspended, of course. Automatic suspension pending the Standard Operating Procedures enquiry because I fired two rounds from my weapon. And because I killed Asad Khan. But I’m not going to be in trouble. I followed SOP to the letter. I shouted a warning at the armed man who had just murdered DS Stone and who would have murdered again if he had the chance. I did what I’m trained to do. I even did my best to avoid over-penetration.’

He smiled at me, happy to be beyond the reach of those who would prosecute policemen for murder.

‘Over-penetration is when a bullet goes into someone and straight out the other side,’ he explained. ‘Best way to avoid over-penetration is to shoot the target when they’re flat on the ground. And that’s what I did with my second shot. And that’s what I told them. And that’s what everyone saw – including you, right?’

I nodded. ‘That’s what I saw,’ I confirmed. ‘I’m glad you’re in the clear, Jackson.’

‘I fired two shots – a double tap – and then I stopped,’ he said. ‘SFOs need to know two things – when to start firing and when to stop. So I’m not in trouble, Max. You don’t have to worry about me. I’m all right. It’s the other part of the story we have to get straight.’

I looked around the pub.

Many of the men had plastic bags at their feet, full of pork chops, beef ribs, legs of lamb. And I saw now that though the men all wore white coats, and they were all smeared with blood, they were all smeared with different measures of blood.

Some of their coats were almost pristine white, flecked with a few discreet little Jackson Pollock flourishes. These were the wholesalers. And some of the men had been cutting up pigs, which are carved while hanging up, reducing the blood splatter. These had only modest amounts of blood on their coats. And then there were the men whose white coats were stained deep red with blood. They had been cutting lamb – meaning they had been cutting towards themselves, as lambs are cut on blocks. So they were all marked with different kinds of blood.

But every one of them wore a sky-blue ribbon on his white coat, as they remembered the forty-five innocent souls who had died when that helicopter came down.

I looked back at Jackson. He had not stopped staring at me.

‘They will ask you about when DS Stone was murdered, but we don’t have to worry about that,’ he said. ‘What we have to work out is what you tell them about what happened in the basement.’

‘We don’t have to work it out, Jackson. There’s nothing to work out.’ I leaned closer to him. ‘You talk to your friend DC Vann?’

‘I wouldn’t call him a friend, Max. But he doesn’t need to be my friend. Ray Vann’s part of our mob. And this mob, Max, they remind me of the mob I was with in Afghanistan. You know what we fought for in Afghanistan? It wasn’t freedom. It wasn’t democracy. It wasn’t Queen and country. It was each other. And it’s the same here. We fight for each other.’

‘Did Vann ask you to come and see me?’

‘He didn’t have to.’

‘Why did Stone speak to him?’

‘When?’

‘In the jump-off van on our way to Borodino Street. Vann was the only member of the team that Alice Stone spoke to. “You OK, Raymond?” As if she was worried about him. As if she was concerned about – I don’t know – his mental state, his stability. She didn’t speak to anyone else. Why did she speak to Vann?’

Jackson sipped his sparkling mineral water, looking away.

‘I didn’t clock it. Must have been checking my kit. Getting in the zone.’

‘What’s Vann’s background?’

‘Shots tend to come from two places, as you know. You’ve got the country boys – and girls – who grew up with guns, shooting clay pigeons, pheasants and peasants. All those rural pursuits. And then you’ve got the ex-servicemen. The ones who got their training in the military. In a different sort of field from the ones they shoot pheasants in. And that was Ray Vann. He was in Iraq. Did well under fire, apparently.’

‘So he was highly trained and he knew what he was doing?’

‘Yeah.’ His eyes slipped away from mine again. ‘But to be honest, you never know.’

‘What does that mean, Jackson?’

‘The ones that grew up with guns – like Alice Stone, for starters – have not had the same life experiences as the ones who served. Ex-servicemen – we’re like rescue dogs, Max. You never know exactly what we have been through. And what it did to us.’

We were silent for a while.

‘What happened in that basement, Max?’

‘What does Ray Vann say happened?’

‘The target went for his weapon.’

‘Is that Vann’s story?’

‘That’s what he told us at the hot debriefing in the immediate aftermath. And that’s what he is going to tell the IPCC.’

The IPCC is the Independent Police Complaints Commission. They have the authority to decide if a firearms officer who discharges his weapon should get a medal or be prosecuted for murder.

And now Jackson looked at me.

‘What are you going to tell them, Max?’

‘Did the Search Team find a weapon in that basement?’

‘No. There were no weapons found on the premises in Borodino Road beyond the assault rifle used for the murder of DS Stone.’

‘Then how did Adnan Khan reach for a weapon if there was no weapon found in the basement?’

‘Vann thought that a known terrorist was reaching for his weapon, OK? You know – one of the bastards who murdered – what is it now? Forty-five? – innocent men, women and children. Don’t forget the children, Max. Vann had to make that judgement in a fraction of a split second to save his own life and the lives of many more.’

‘CTU say that the only weapon on the premis

e was the AK47 that killed Alice Stone. No grenades. No other weapons.’

I watched my friend’s spine stiffen as something flared up inside him.

‘Can we please all stop saying that Alice was killed? Or that she died? She was murdered, OK?’ he said, as if I had disputed the fact. He took a breath. ‘Down in the basement the last of the Khan brothers went for what DC Vann thought was a weapon, OK? Khan made a sudden, violent movement and so Vann shot him. That’s what he is going to tell the IPCC when he talks to them first thing tomorrow.’

I sipped my beer and said nothing.

‘They will talk to you, too, Max. You know they will! There were only three men in that basement. One of them is dead. The IPCC will have a chat with you and Vann. And you have the power to corroborate his version or tell a different story.’

He raised his mineral water in salute.

I stared at him and said nothing. I drank my beer. The pub was very loud.

‘I know you’re solid, Max.’

I held up a hand for silence.

‘You don’t have to worry about me,’ I said.

‘I know that, Max. Do you think I don’t know that?’

‘I’m not going to rat him out.’

I looked at my beer. I wanted to get home. I wanted to see my daughter sleeping. I wanted this long hard day to be behind me.

‘But I’m not going to lie for him,’ I said.

Jackson’s face hardened.

‘What’s that, Max? Like some kind of personal code of honour or something?’

I shrugged.

‘Call it what you like. I’m not going to rat him out, but I’m not going to lie for him.’

‘They finally reached Alice Stone’s husband,’ Jackson said, the anger mounting.

‘I know.’

‘Her husband’s a copper. New Scotland Yard. Got two little kids under the age of five. A boy and a girl. When they grow up, they’re not even going to remember her, are they? They’re not even going to remember their mum, Max! Because they were too little when their mother was murdered.’

‘I’m not going to rat him out, but I’m not going to lie for him,’ I repeated for the third and final time, just making sure we were clear here.

I bolted the remains of my beer and stood up.

‘Come back soon, Jackson. Train with me at Fred’s. Come and see Scout. Cook for us again. Walk Stan. I miss you. I do. You’re the only brother I ever had.’

He was waiting for the rest of it.

‘But don’t you ever lean on me again,’ I told him.

7

The next day was Saturday and I breathed out.

I woke up to sunlight pouring through the bedroom skylight and the best sound in the world.

Stan was snoring on the pillow next to me, his left ear a silky curtain falling across his eyes. As I sat up he stirred in his sleep, smacked his lips, but did not wake. I stared at his face, noting how the black smudge under his nose extended across his mouth to his chin before giving way to the smudge of white on his chest, like a tiny tuxedo shirt. Everything else about his fur was a shade of red, from the strawberry blond feathers of his tail and legs to the deep russet of his coat and ears and head.

I once looked at a sleeping woman in this much adoring detail.

But now it was a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel.

It had been a long march for Stan to reach that pillow. At first he had been kept in his cage at night. Then he was allowed to roam the loft after lights out. And now he had made it all the way to my bed.

He shrugged with irritation in his sleep as I threw back the duvet, got down on the floor and pumped out a brisk twenty-five press-ups. When I stood up to flex my leg, feeling how time and Fred were slowly but surely healing it, Stan opened his large round eyes and considered me impassively.

He did not move as he watched me stretch and then do another twenty-five press-ups – slower this time, thinking about form now, the pain in my knee a steady but distant throb. Then I stretched again, and as I did the third set of twenty-five press-ups Stan closed his eyes, sighing contently as he slipped back into deep sleep.

By the time I did the final set of twenty-five press-ups – the hard set, the one where the lactic acid burns in shoulders and arms, the set that actually does you some real good – the dog was snoring loudly once more.

I went into the main room and turned on the TV to see what was happening in Borodino Street.

And there was the by-now familiar vantage point of the street viewed from a news helicopter, but where the road should have been there was nothing but flowers. It was early Saturday morning, and the crowds, kept on the pavement by two long lines of uniformed officers were already out in force.

The picture cut to a close-up of the crowd. A small child, a girl, was being led by the hand as she laid her bouquet with all the rest. The camera pulled in tighter on one of the photographs placed among the flowers.

DS Alice Stone was smiling for all eternity. The image had become one of the favourite shots of Alice, taken on holiday in Italy just after the birth of her first child. She looked giddy with happiness. And now the crowds came to mourn her.

I understood their grief because I felt it too. But the outpouring of emotion for Alice Stone was still bewildering. This was one woman who was being mourned by people who had never met her in a way that the forty-five victims of Lake Meadows were not mourned by total strangers. Perhaps the loss of all those people was simply too much to comprehend, I thought. All those lives stolen in a moment. All those lost fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, husbands and wives. All those families torn apart, all that grief that would echo through generations. It was too terrible to grasp.

But we all understood what had been lost in Alice Stone. The death of this one police officer who had lost her life because she sought justice for what happened at Lake Meadows – this tough, smart and beautiful woman, a wife, a mother and a daughter – had come to represent all the innocent victims of the summer. The loss of Alice Stone was like an ache in the heart of the nation.

When the camera cut back to the helicopter’s eye to take it all in – the sea of flowers, the grim-faced crowds, the house hidden behind huge white screens where the CSIs and search teams were finishing their work – I saw him for the first time.

He was at the end of the street, just beyond the police perimeter, a lean, long-limbed young man in a suit and a bow tie who appeared to be standing on some kind of small box. He was addressing a section of the crowd and I noticed them because they had their backs turned to the flowers, and the house and the spectacle of Borodino Street.

The young man on his box was not the only speaker. Further back, at the very edge of the crowds, a black priest was addressing a small makeshift congregation of perhaps a dozen people. Even from this distance, you could make out his dark clerical robes, the white dog collar. But when he knelt to pray, half of his flock turned away, and wandered towards the young man on the box.

It was impossible to know what he was saying and why he had them rapt. It looked like he was giving his own kind of sermon. And the priest could not compete.

I called Edie Wren, not taking my eyes from the TV screen.

‘Edie, are you watching this on TV?’

‘Max?’ I had woken her.

I felt bad about that but I needed to understand what I was looking at in Borodino Street. Who was this guy?

‘Turn on your TV,’ I said. ‘There’s some guy talking to the crowd outside the Khan house. It looks like – I don’t know – it looks like he’s preaching to them.’

‘Max.’ She was awake now.

‘Are you watching it?’

‘Max – forget about it all for a while, OK? I know you were in the middle of it when that Air Ambulance came down. I know you saw Alice Stone die. I know you will never forget any of it. Of course I bloody do. But none of it is our investigation. Let it go, Max.’

‘You haven’t turned on your TV?’

I couldn

’t pretend I was not disappointed.

‘Enjoy your weekend, Max,’ Edie said, fully awake now. ‘You and Scout and Stan. Try to put Lake Meadows out of your head. Forget about Borodino Street for a while. I know it’s hard. But you’ve done your bit, Max. Now let someone else deal with it.’

And then I heard the man in her bed, his voice thick with sleep, stirring next to her.

‘Who is it?’

I felt embarrassed, humiliated and stupid.

Mr Big. Edie’s married man.

I wondered how he swung this at home, what smooth lie he had told to be given an overnight pass on the night before the weekend. Friday night, Saturday morning. A business trip, I thought. It had to be a business trip.

‘Work,’ Edie said, and somewhere in my thick head I could see it all.

Her face turned away from the phone. The man in her bed.

‘Max?’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ I said. ‘Sorry. See you Monday.’

I sat down in front of the TV.

It was hypnotic. The sight of a nation in mourning. We mourned the victims of the latest atrocity at Lake Meadows, and we mourned all those who had died in previous attacks, and we mourned all those who would die in the future. And we mourned Alice Stone.

Everyone knew her now. Everyone knew about her copper husband, her two small children, her idyllic childhood in the Lincolnshire countryside. Everyone knew her smile. The country was haunted by that smile.

I watched TV until Scout wandered out of her bedroom. Then I turned it off and I followed her into the kitchen even though I knew that she could make breakfast for herself now – using a step stool to remove the loaf from the cupboard and butter and orange juice from the fridge, growing up faster than scheduled, the way that the children of divorced parents always will.

‘You want me to make some breakfast for us, Scout?’

A sly smile. ‘Today I’m making breakfast for you.’

So I went downstairs to get the mail.

There were the two magazines I subscribed to, Boxing Monthly and Your Dog, and an assortment of bills, junk mail about PPI and flyers offering pizza and Phad Thai delivered to your door. A smiling Gennady Golovkin was on the cover of Boxing Monthly and a grinning Labrador Retriever was on the cover of Your Dog. It was only when I was back in the loft that I realised there was also a card from my ex-wife.

Long Gone the Corroboree

Long Gone the Corroboree #taken

#taken The Family Way

The Family Way One For My Baby

One For My Baby Man and Boy

Man and Boy The Murder Bag

The Murder Bag Return to Moondilla

Return to Moondilla Beyond the Bounty

Beyond the Bounty Die Last

Die Last The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe)

The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe) Stories We Could Tell

Stories We Could Tell Return to the High Country

Return to the High Country Silver in the Sun

Silver in the Sun My Favourite Wife

My Favourite Wife Dead Time

Dead Time Girl On Fire

Girl On Fire Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood

Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood Catching the Sun

Catching the Sun The Slaughter Man

The Slaughter Man Men from the Boys

Men from the Boys Man and Wife

Man and Wife Valley of the White Gold

Valley of the White Gold Back to the Pilliga

Back to the Pilliga The Call of the High Country

The Call of the High Country Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe

Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe