- Home

- Tony Parsons

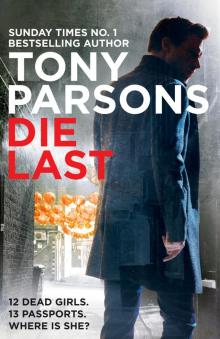

Die Last

Die Last Read online

Contents

About the Book

About the Author

Also by Tony Parsons

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue: The Girl from Belgrade

Part One: The Woman Who Fell Through the Ice

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part Two: Shadow People

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Part Three: The Girl in the Cab

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Copyright

About the Book

12 DEAD GIRLS.

As dawn breaks on a snowy February morning, a refrigerated lorry is found parked in the heart of London’s Chinatown. Inside, twelve women, apparently illegal immigrants, are dead from hypothermia.

13 PASSPORTS.

But in the cab of the abandoned death truck, DC Max Wolfe of West End Central finds thirteen passports.

WHERE IS SHE?

The hunt for the missing woman will take Max Wolfe into the dark heart of the world of human smuggling, mass migration and 21st-century slave markets, as he is forced to ask the question that haunts our time.

What would you do for a home?

About the Author

Tony Parsons left school at sixteen and his first job in journalism was at the New Musical Express. His first journalism after leaving the NME was when he was embedded with the Vice Squad at 27 Savile Row, West End Central. The roots of the DC Max Wolfe series started here.

Since then he has become an award-winning journalist and bestselling novelist whose books have been translated into more than forty languages. The Murder Bag, the first novel in the DC Max Wolfe series, went to number one on first publication in the UK. The Slaughter Man and The Hanging Club were also Sunday Times top five bestsellers.

Tony lives in London with his wife, his daughter and their dog, Stan.

Also by Tony Parsons

The Murder Bag

The Slaughter Man

The Hanging Club

Digital Shorts

Dead Time

Fresh Blood

For Rob Warr of Highbury, Muswell Hill and Hove

‘How often have I lain beneath rain on a strange roof, thinking of home.’

William Faulkner, As I Lay Dying

PROLOGUE

The Girl from Belgrade

The first thing they took was her passport.

The man jumped down from the cab of the lorry and snapped his fingers at her.

Click-click.

She already had her passport in her hands, ready for her first encounter with authority, and as she held it out to the man she saw, in the weak glow of the Belgrade streetlights, that he had a small stack of passports. They were not all burgundy red like her Serbian passport. These passports were green and blue and bright red – passports from everywhere. The man slipped her passport under the rubber band that held the passports together and he slipped them into the pocket of his thick winter coat. She had expected to keep her passport.

She looked at him and caught a breath. Old scars ran down one side of his face making the torn flesh look as though it had once melted. Then the man clicked his fingers a second time.

Click-click.

She stared at her kid brother with confusion. The boy indicated her suitcase. The man wanted the suitcase. Then the man with the melted face spoke in English, although it was not the first language of either of them.

‘No room,’ he said, gesturing towards the lorry.

But she gripped her suitcase stubbornly and she saw the sudden flare of pure anger in the man’s eyes.

Click-click, went his fingers. She let go.

The suitcase was the second thing he took. It was bewildering. In less than a minute she had surrendered her passport and abandoned her possessions. She could smell sweat and cigarettes on the man and she wondered, for the first time, if she was making a terrible mistake.

She looked at her brother.

The boy was shivering. Belgrade is bitterly cold in January with an average temperature of just above freezing.

She hugged him. The boy, a gangly sixteen-year-old in glasses that were held together with tape on one side, bit his lower lip, struggling to control his emotions. He hugged her back and he would not let her go and when she gently pulled away he still held her, a shy smile on his face as he held his phone up at head height. They smiled at the tiny red light shining in the dark as he took their picture.

Then the man with the melted face took her arm just above the elbow and pulled her towards the lorry. He was not gentle.

‘No time,’ he said.

In the back of the lorry there were two lines of women facing each other. They all turned their heads to look at her. Black faces. Asian faces. Three young women, who might have been sisters, in hijab headscarves. They all looked at her but she was staring at her brother standing on the empty Belgrade street, her suitcase in his hand. She raised her hand in farewell and the boy opened his mouth to say something but the back doors suddenly slammed shut and her brother was gone. She struggled to stay on her feet as the lorry lurched away, heading north for the border.

By the solitary light in the roof of the lorry, she saw there were boxes in the back of the vehicle. Many boxes, all the same.

Birnen – Arnen – Nashi – Peren, it said on the boxes. Grushi – Pere – Peras – Poires.

‘Kruske,’ she thought, and then in English, as if in preparation for her new life. ‘Pears.’

The women were still staring at her. One of them, nearest to the doors, shuffled along to find her space. She was some kind of African girl, not yet out of her teens, her skin so dark it seemed to shine.

The African gave her a wide, white smile of encouragement, and graciously held her hand by her side, inviting the girl from Belgrade to sit down.

She nodded her thanks, taking her seat, and thinking of the African as the kind girl.

The kind girl would be the first to die.

Eight hours later the women stood outside a service station, taking turns in the cracked and broken bathroom in a last desperate attempt to keep clean.

The girl from Belgrade looked at the cars on the motorway. The winter sun was rising milky white on what looked like miles of farmland, as barren as the surface of the moon.

‘What country is this?’ she said.

‘Austria?’ said one of the young women in the hijabs. ‘Germany?’

‘A rich country.’

The man came out of the toilet, pulling up the zip of his trousers with one hand and clicking his fingers with the other.

Click-click.

‘No more,’ he said, and the women must have looked confused. He impatiently snapped his fingers in their faces. ‘No stops no more,’ he explained, rolling his eyes at their inability to understand his fluent English.

Soon they were back on the motorway.

‘No stops,’ the kind girl said, her face splitting in that wide white smile. ‘No suitcase. No time.’

‘No parking!’ the girl from Belgrade laughed.

‘No smoking!’ said an Asian woman.

One of the women in a hijab waggled her dead phone. ‘No signal!’

They all laughed together. It was the last time they laughed. For it was cold inside the lorry now, far colder even than midnight in Belgrade in January. At first she thought it was because the ground was steadily rising and they seemed to be passing through mountains.

But then she saw the steam on the breath of the other women.

The cold was not outside the lorry.

The cold was inside the lorry.

And it was getting colder by the moment, far too cold to sleep.

And in the end, far too cold to live.

The girl from Belgrade shivered. Even the air was freezing. It hurt her eyes.

She touched the metal door next to her and it was so cold that it burned her fingertips.

The blood drained from her hands, flooding deeper into her body, trying to protect the organs that kept her alive, and she felt that the icy air had seeped into her blood like poison.

She stamped her feet, flexed her hands, trying to bring some warmth to them, some movement, some life.

The kind girl was looking at her.

‘So cold,’ the girl from Belgrade said, feeling foolish for stating the painfully obvious.

But the kind girl nodded.

‘Yes. Share my gloves.’

‘No, no.’

‘Please, sister. Put your hands inside with me.’

And so they sat like that for a while, with her numb hands squeezed together inside the kind girl’s gloves, palms pressed against palms.

But then her feet began to hurt. And it was so much more than cold. It was the presence of a blinding, aching pain. As she stamped her feet, she felt the muscles in her neck and shoulders tighten. She moved her head in a horizontal figure of eight, the way she had seen her mother do when her neck was tight, and it made not the slightest difference. She saw the kind girl begin to shiver and watched with silent horror as the shivering became a kind of trembling.

She looked around at the other women. One of the women in a hijab was already in something deeper than sleep.

She looked at the kind girl and saw that there were icicles hanging from her thick black eyelashes and the sight of them sent a flood of terror through her.

She stood up, abruptly pulling her hands free from the kind girl’s gloves, suddenly aware that the freezing cold that first gripped her hands and feet had now spread everywhere.

Everything was tight. Everywhere hurt. She began to shake with dread.

They were all going to die in here.

She banged on the windowless slab of steel that separated the back of the lorry from the driver’s cab. She could smell cigarettes. She could hear voices. A man and a woman.

She banged harder.

The lorry kept going.

But she kept banging on the wall of the driver’s cab, the other women silent behind her, although some of them were watching her with half-closed eyes.

And still the lorry kept driving.

Long after she had given up and slumped down next to the kind girl – was it hours or minutes? – the lorry finally stopped. She could hear the sound of big diesel engines, distant voices and – was she dreaming? – what sounded like the horn of a large ship.

She got on to her numb feet and stood alone at the back of the lorry and hammered the door until her hands were bruised and bloody. But the man who drove was as good as his word.

The doors remained closed.

Eventually the lorry pulled off again.

The cold had reached her brain now. She dropped to the floor. Her mind was cloudy. She was going to do something very important – she was certain of that – but now the plan had somehow fled from memory. She stood up and stared at the other women, dumbfounded. What was this glacial fog inside her head? She was very afraid now – a wild, unnameable fear that skittered across her heart and clenched her teeth.

And she had the urge to pee.

And her fingers were covered in small blisters.

And she was very tired.

Above and beyond everything else, there was exhaustion like nothing she had ever known. She sank to the floor again and knew that she would not be getting back up.

Her eyes were closing. She needed to sleep.

As her eyes were closing, she looked around at the unfamiliar faces.

Where was her brother? Why were they apart? They had no one in the world but each other. They should have stuck together. Where was that boy? She would remember if she could only concentrate. Sleep now, she thought. Worry about it all after your long sleep.

It was only the voice of the kind girl that pulled her back.

‘Would you please hold me, sister?’

Her eyes jerked open and she stared at the kind girl without recognising her face, although suspecting she had seen it somewhere before.

Now the trembling was more violent and her entire body spasmed with a terrible will of its own. There was a young Asian woman sitting directly opposite and her eyes were wide open and yet she was sleeping. And she knew, somewhere deep inside her foggy mind, that it was the sleep without end.

The faces of the other women seemed to melt in the darkness, dissolving into shapes that had nothing to do with human faces. Then one of the women stood up and began removing her clothes. Ripping at them, not bothering with buttons, desperate to be free of them.

‘I am burning,’ the woman said in English, and then abruptly sat down, curled into a foetal ball and closed her eyes.

The girl from Belgrade stared dumbly at the boxes that seemed to crowd in on them. Birnen – Arnen – Nashi – Peren, said the boxes.

Grushi – Pere – Peras – Poires. Pears in what felt like every language except for Serbian, every tongue on the planet except her own.

What was the word for the fruit in Serbian?

‘Kruske,’ she said out loud.

She could hear her mother calling, saying her name loud and clear, even though her mother was five years in the grave.

How could these things be? How were they possible?

Sleep now, she told herself, and think about it all later.

But the voice pulled her back again.

‘Please, sister. Hold me now.’

So she held the kind girl – she had forgotten to do it before – and she kept holding her, long after the kind girl’s trembling had stopped. It was all silence in the back of the lorry now and the silence was matched in the world outside, for at some point in the endless night, the lorry had stopped, and remained stopped, even though nobody came to open the door.

She could no longer see the steam of her breath. Indeed, she was no longer aware of the need to breathe.

And as the kind girl died in her arms, she suddenly understood. Dying is easy.

Living is hard.

PART ONE

The Woman Who Fell Through the Ice

1

We thought we had a bomb.

That’s why Chinatown was deserted. If the public thinks the police have found a dead body then they get out their phones and settle down for a good gawp, but if they think we have found a bomb then they will get on their bikes.

The lorry was outside the Gerrard Place dim sum restaurant that marks the start of London’s Chinatown, parked at an angle with its nearside wheels up on the pavement.

The lorry itself looked no different to the convoy of lorries that were lined up bumper to bumper all down one side of Gerrard Street, making their early morning deliveries to the shops and restaurants of Chinatown. But half up on the pavement and parked at a random angle, this lorry looked dumped, as if the driver couldn’t get away fast enough, and that makes our people think only one thing.

Bomb.

Under the bobbing red la

nterns that hailed the lunar new year, Chinatown was abandoned apart from armed response officers in their paramilitary gear, paramedics from half a dozen hospitals, firemen from the station on Shaftesbury Avenue, uniformed officers from New Scotland Yard, detectives from Counter Terrorism Command, dogs and their handlers from the Canine Support Unit, and our murder team from West End Central, 27 Savile Row, a short walk from Chinatown.

It was actually a lot of people, all wound up tight, and our breath made billowing clouds of steam in the bitterly cold air. But there was nobody who was not meant to be there.

The public – the deliverymen to Chinatown, the early workers cutting across Soho to their offices in Mayfair or Marylebone or Oxford Street – had scarpered as soon as the police tape went up and the word went out. Only one local was still here – the elderly Chinese man who had seen the lorry and dialled 999. He was a short, sturdily built man who had probably spent a career carting crates of Tsingtao beer into the stores and restaurants of Chinatown, and there was a hard-earned toughness about him despite the modest frame.

The weak winter sun was still struggling to rise above the rooftops. January’s feeble attempt at a sunrise. Without looking at my watch, I knew it must be around eight by now. I sipped a triple espresso from the Bar Italia, my eyes on the abandoned lorry, as DC Edie Wren interviewed the Chinese man.

‘So you didn’t see the driver?’ Edie asked him.

The man shook his head. ‘As I believe told you, Detective, I saw no sign of the driver.’

His accent was a surprise. He spoke with the buttoned-up formality of a BBC radio announcer from long ago, as if he had learned his English listening to the World Service.

‘Tell me again,’ Edie said. ‘Sir.’

‘Just the lorry.’ He gestured towards it. ‘Parked on the pavement. The driver was already gone.’

‘Was the driver Chinese?’

‘I didn’t see the driver.’

Edie paused.

‘You’re not protecting anyone, are you, sir?’

‘No.’

Edie stared hard at the old man.

‘Do you have permission to be in this country, sir?’

The man, never tall, straightened himself up to his full height, his back stiffened with wounded pride.

Long Gone the Corroboree

Long Gone the Corroboree #taken

#taken The Family Way

The Family Way One For My Baby

One For My Baby Man and Boy

Man and Boy The Murder Bag

The Murder Bag Return to Moondilla

Return to Moondilla Beyond the Bounty

Beyond the Bounty Die Last

Die Last The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe)

The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe) Stories We Could Tell

Stories We Could Tell Return to the High Country

Return to the High Country Silver in the Sun

Silver in the Sun My Favourite Wife

My Favourite Wife Dead Time

Dead Time Girl On Fire

Girl On Fire Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood

Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood Catching the Sun

Catching the Sun The Slaughter Man

The Slaughter Man Men from the Boys

Men from the Boys Man and Wife

Man and Wife Valley of the White Gold

Valley of the White Gold Back to the Pilliga

Back to the Pilliga The Call of the High Country

The Call of the High Country Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe

Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe