- Home

- Tony Parsons

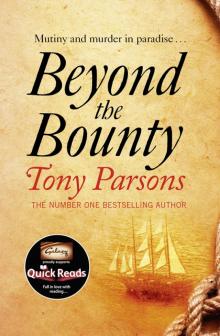

Beyond the Bounty

Beyond the Bounty Read online

Beyond the

Bounty

Tony Parsons

For my father, the old sailor who told me, ‘One hand for the ship – one hand for yourself.’

Author’s Note

The mutiny on HMS Bounty occurred in the South Seas on 28th April 1789.

Eighteen sailors led by Fletcher Christian rose up against the ship’s cruel commanding officer, Captain William Bligh.

The men who joined the mutiny set Captain Bligh and those loyal to him adrift in a small boat, many thousands of miles from the known world.

After sailing further, the mutineers settled on the island of Pitcairn, which was not yet on any map. Here the Bounty was burned to stop it being found by the Royal Navy.

Nearly twenty years later the American trading ship Topaz discovered the secret community on Pitcairn. They found nine women, many children and just one man left alive.

This is his story.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Author’s Note

1. A Mighty Fire

2. The Angry Widow

3. Wives of the Bounty

4. The Last of the Rum

5. The Woman on the Cliff

6. Crime and Punishment

7. The Shipwrecked Sailor

8. The Best Time

9. Civil War

10. King of the World

About the Author

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

A Mighty Fire

Our ship, the Bounty, was made of English oak and it made a mighty fire.

We watched her burn from the shore of the tiny island. She was the ship that had been our home, our prison and our mad dream of freedom. The ship that had carried us to the end of the world.

It burned.

And before this night was over, our captain would burn with it.

The night was full of the sound of the animals we had brought ashore and the crackle of burning wood. But there were no human sounds. Not until our captain howled with pain.

‘You burn our ship?’ cried Fletcher Christian. ‘You fools! Then how will we ever go home?’

We watched him row out to the Bounty. We made no move to help or to hinder him. We just stood watching on the narrow beach of soft sand at the bottom of steep white cliffs.

What a strange little party we were – eight English sailors from the Bounty, six men and eleven women from Tahiti, one of them with a babe in arms. After our many adventures on the rocky road to Eden, and after leaving some of our fellow sailors on Tahiti, that was all that we had left to build a new world. One of the women was crying. This was Maimiti, daughter of the King of Tahiti, a great beauty and wife of our captain, Fletcher Christian.

We saw him reach the Bounty, climb on deck and go below. He stood out like a little black insect against the flames. We watched him throw useless buckets of water on the burning masts, the flaming sails and the smoking deck.

We knew it was a battle that he could never win. When his clothes began to smoke and flame, we knew he knew it too.

We watched him come back. Slowly, wearily. Rowing with the good arm he had left.

There was not much to be done. He was badly burned and the life was already ebbing out of him. We lay him down on that narrow sandy beach. We gave him water. The women comforted his wife.

And I held him as he died.

Some of the men wept.

The Tahitians who thought he was some kind of god. And even a few of the English seamen, who also placed him high above other men.

I held him, but I was dry-eyed. Because I had never liked Fletcher Christian.

Mister Fletcher Christian.

That’s always what he was to me – Mister Fletcher bloody Christian.

From the first moment I saw him, looking dapper in his fine midshipman’s clothes on the deck of HMS Bounty as we set sail on 23rd December 1787 from Spithead, to the last moment I saw him dying of those terrible burns more than two years later on the beach of Pitcairn.

I never cared for the fellow.

Oh, I know the ladies in smart drawing rooms back in London probably still get all weepy when they think of Mister Fletcher Christian – so tall, so handsome, so doomed. And I knew men who would have followed Fletcher Christian to the gates of hell and beyond.

But he was not for me.

I knew him. Not the legend but the man. I saw his kindness and his courage when he faced down our first captain, William Bligh.

I knew Fletcher Christian and I choked on the smell of his burning flesh as he died in my embrace. And I could see clear enough what the rest of the world saw in him too.

He was blue-eyed and fair-haired, broad-shouldered and topping six foot. Clean of mind – at least until he fixed his telescope on those Tahitian maids – and clean of limb. Brave as a young lion.

He stood up to Bligh’s foul cruelty when it would have been the easy thing to go below deck and puff his pipe and read his Bible. Instead Fletcher Christian led us, and he steered the Bounty and the mutineers into history.

Even at the moment of his death, Fletcher’s heart was made of the same sturdy English oak as our ship. But I believe that we broke his heart when we torched the Bounty as she lay in the bay.

We burned her to avoid detection. We burned her to prevent desertion.

And most of all we burned her to avoid Fletcher Christian having the bright idea of going home to dear old England to explain our actions to some judge who would hang us all.

For that was what he wanted – our leader, our young lion, our Mister Fletcher Christian – he wanted to explain our mutiny to those in England.

The rest of us were willing to settle for watching fifty years of sunsets with some Tahitian maid under a palm tree. And keeping the hangman’s rope from our mutinous necks.

But he was good, you see.

Mister Fletcher Christian. A good man. An honest man. They all loved that goodness in Fletcher Christian, even as he burned to a crisp under the tropical moon.

The men. The women. The world. But what they loved about Mister Fletcher Christian was what made me, in some secret chamber of my heart, turn away from the man.

For it was the very goodness of Mister Fletcher Christian that stuck in my throat. He carried his goodness around like a bloody halo, expecting the rest of the world to give it a polish every now and then. He carried his goodness like Christ with his cross on the road to Calvary.

And our captain was crucified upon that cross.

Mr Christian – was ever a legend more fittingly named? – thought he was better than other men.

More moral. More noble. More good.

Perhaps he was right. Perhaps.

He certainly always thought it. He had the rock-solid confidence of the upper-class Englishman.

A bit of a snob, our Mister Christian.

He may have believed that our first cruel captain, Bligh, was wicked and evil and a monster. It is true that Bligh would smile at the sight of the whip being brought out as if it was the sun breaking through grey clouds, or an orange in a stocking on Christmas Day.

But I reckon that Fletcher Christian also believed that William Bligh was from the gutter.

I reckon that Mr Christian thought that rough William Bligh was little better than the scum and rascals who made up the crew of the Bounty on our mad mission to bring back breadfruit from the South Seas of the Pacific Ocean.

Fletcher Christian looked down on William Bligh. And he would have looked down on Bligh even if he had spoon-fed us rum from dawn to dusk.

Still, Fletcher Christian was impressive. I will give him that.

They are buil

ding their bloody Empire on the likes of Fletcher Christian. They think that men like him (the brightest, the best) are leading the likes of me (the rankest, the worst).

Fletcher sipped his port. The men got roaring drunk on rot-gut rum. Fletcher fluttered his eyelashes at the ladies. We whored. Fletcher was a cultivated man. We could just about make our mark if you were to guide our hand. You get the picture.

Fletcher Christian was a gentleman.

More than us. And more than Bligh. But better than the rest of us? Mister Fletcher Christian clearly thought so.

But in my experience of this wicked world, all men are much the same.

The Bounty burned all night.

As the sun came up over the South Seas, the ship that had carried us so far was meeting its end in flames fifty feet high.

It was a day as close to Paradise as I ever saw in this world. The sky above the island was so blue that it made your heart ache to behold such beauty.

A soft breeze was moving through the palm trees like a mother’s sigh. And the heat – it was that soothing heat that we found on the island, that calming heat we found at the end of the world.

Even as I held my dying captain in his final minutes, I was not sorry that we had burned the Bounty. Because we wanted this Eden to last.

We did not want to go back to England. There, we would have to tell our story and to make our case. To throw ourselves at the dubious mercy of some bewigged bastard of a judge.

After much careful reflection, we had no wish to sail back to England and face justice that would have had us all dangling on the end of a rope. We would hang – twitching and shitting and eyes bulging, our tongues turning black as our dear old mothers wept and the crowd roared with delighted laughter.

Go back to that?

No thank you, Mister Christian, sir.

But his goodness was calling him back to England. And then his goodness called him to that burning ship. And finally his goodness was calling him to Heaven.

‘Ned, I am done for,’ he croaked. ‘Tonight I shall walk the streets of glory, and sit with angels in the realm of the Lord.’

You could see he was quite looking forward to it. The angels. The clouds. The business of comparing halos. The way he told it, dying was like shore leave that lasted for all eternity. Without the pox and the sore heads. You could see the attraction.

Then he writhed and twisted with that terrible pain. Fire is a terrible way to go. Give me water. Give me my lungs full of salt water in Davey Jones’ locker for a year rather one minute of the pain that Mister Fletcher Christian endured at the end of his short and famous life.

The men were crying. The women too. The men were crying like women and the women were crying like banshees. What a racket! I had to bark at them to shut their traps. For I could hardly hear the words of the dying man in my arms.

‘Ned,’ he said. ‘Oh, Ned Young. Why did you do it? Oh, how could you burn our proud Bounty?’

‘Because we can’t go home, sir,’ I blubbered. Now the rest of them had started me off and I was sobbing like a milkmaid who has had her best bucket hidden by a stable lad. ‘Because we can’t go home where nothing is waiting but the rope.’

‘No, Ned – it is still our old and beloved England,’ he gasped. ‘Justice, Ned. The truth.’ He fought for breath here, for he was overcome by the pain. ‘What is right and what is wrong,’ he continued. ‘Standing for liberty against tyranny. Standing for Christian values in the face of all that is cruel and wicked. That was our choice – the way of Captain Bligh or my way, Ned.’

As though all goodness and right belonged to him alone. He coughed a bit at this point. Mostly blood, although also some yellow substance which did not look too promising.

‘They would have listened,’ says he.

‘They would have listened, all right,’ says I. ‘They would have had a good old listen and then they would have made us dangle.’

But even a cold, hard-hearted scoundrel such as myself could not fail to be moved by the death of Mister Fletcher Christian.

My eyes ran with tears and I knew that, despite everything, I loved him.

Not that I ever liked him much.

But I can’t deny that I loved him.

I could feel the fire in my blood. The Bounty crackled and shrieked like a living thing. It died hissing and spitting as it dropped its masts into the boiling water. And then, just as the sky was turning pale pink in the east, the Bounty collapsed beneath the sea.

For a few minutes there were wispy trails of grey smoke curling from the surface, and then they were gone too.

It was as if our ship had never existed.

‘Ned,’ Fletcher Christian whispered. And it was no more than a faint whisper now, this close to the end. ‘Don’t leave me. Don’t let me go alone, Ned.’

‘I’m here,’ I sobbed, holding him as tight as I could without causing him even more pain. ‘I’m here, and here I will stay. I shall not go until you are gone. I promise you that. You have my word, Mister Fletcher Christian, sir.’

‘Oh, Ned,’ he said. ‘The pain.’

I placed my hand over his nose and mouth. ‘There, there,’ I said. ‘There, there – rest your eyes, Mister Christian, sir. Rest those blue eyes of yours for just a moment, sir.’

His eyes widened as I leaned into him, pushing down harder over his nose and mouth, making quite sure that he would not be breathing much more of that sweet tropical air.

The eyes of Mister Fletcher Christian slowly began to close.

I have big hands, you see.

Big hands made hard by twenty-five years before the mast.

Stopping a dying man from breathing is about as hard for me as it is for your grandmother to fill her pipe.

‘You’re right, sir,’ I said. ‘The angels are waiting for you. They have been waiting all along. You have been right all along, Mister Fletcher Christian, sir. Right about everything.’

Heaven was calling him.

Loud and clear.

Even above the weeping and wailing of the men and the women, and even above the terrible sound of the Bounty dying in the bay, you could hear Heaven calling Mister Fletcher Christian to his reward.

And I confess on these pages that these large and hardened hands of mine helped that good young gentleman on his way.

It felt like the least I could do.

2

The Angry Widow

I climbed to the top of the cliffs and I looked back on our island.

It was like looking at Paradise. Our island, Pitcairn, was Paradise.

Pitcairn is a tiny garden in the middle of an endless ocean. A densely wooded rock in the middle of nowhere. Just two miles square. And the loneliest island in the South Seas.

We had looked for it long and hard before we found it.

The Bounty had visited more than thirty islands before we landed on Pitcairn. Yes, more than thirty islands bobbing in the South Seas, and they all had something wrong with them.

There were islands where the natives thought they might decorate their grass huts by putting our heads on the ends of muddy sticks.

There were islands with so little water we would have died of thirst before the year was out.

There were islands with nothing to eat. Islands with nothing to drink. Islands where the natives came screaming out of the bushes and chased us back to our long boat. We saw them all.

And then we saw Pitcairn, our beautiful island in the sun. The last home that any of us would ever know.

It was a place of rough beauty. The steep cliffs. The jagged rocks in the bay and the wild sea beyond. The craggy green hills. The deep blue of the sea and the lighter blue of the sky.

There was fresh water and food galore. It was uninhabited. And the sea winds made it far cooler than Tahiti.

Pitcairn was perfect.

We almost missed it. We almost sailed right by. Not because it is such a tiny speck in that endless expanse of blue water that men call the Pacific Ocean.

No, we almost sailed straight past our future home because, according to every single map in the King’s navy, Pitcairn was not there.

The maps were wrong.

Pitcairn was charted wrong on the Bounty’s map, which means that it was charted wrong on all of them. Mister Christian spotted it. According to the map, Pitcairn was meant to be 150 miles from where God had seen fit to drop it.

It was too good to be true. The men could scarcely believe their luck. Pitcairn was a paradise that showed itself on no man’s map.

Even old Fletcher had a smile on his dark and handsome chops for once.

We would hide ourselves forever on the only island in the Pacific that, as far as the King’s navy was concerned, did not exist.

It felt as if we had stumbled into the Garden of Eden. The soil was rich and fertile, and there was food galore. Game. Yam. Papaya. Pineapples. Watermelons. Mandarins. Grapefruit. Lemon. Limes. And breadfruit – bloody breadfruit!

We all had a good laugh at the sight of breadfruit.

For breadfruit was the reason for the Bounty’s doomed mission to the ends of the earth. We were meant to bring back a cargo of breadfruit so that it could be fed to the slaves of the West Indies. And if it kept those busy fellows going until teatime then the British powers that be were going to feed breadfruit to the entire Empire.

Captain William Bligh was to be to breadfruit what Sir Walter Raleigh had been to the potato. That was the grand plan. Except the Bounty never made it home.

And the only breadfruit that I ever picked went straight into my belly. Or the sea, when we were throwing them at Bligh’s head as we cast him adrift in his little boat to drown in shark-rotten waters, or get his private parts sliced off by unfriendly natives, or – my guess as to Bligh’s fate – starve to death.

But our diet was now better than anything the King had ever dished up when we served in his navy.

Long Gone the Corroboree

Long Gone the Corroboree #taken

#taken The Family Way

The Family Way One For My Baby

One For My Baby Man and Boy

Man and Boy The Murder Bag

The Murder Bag Return to Moondilla

Return to Moondilla Beyond the Bounty

Beyond the Bounty Die Last

Die Last The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe)

The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe) Stories We Could Tell

Stories We Could Tell Return to the High Country

Return to the High Country Silver in the Sun

Silver in the Sun My Favourite Wife

My Favourite Wife Dead Time

Dead Time Girl On Fire

Girl On Fire Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood

Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood Catching the Sun

Catching the Sun The Slaughter Man

The Slaughter Man Men from the Boys

Men from the Boys Man and Wife

Man and Wife Valley of the White Gold

Valley of the White Gold Back to the Pilliga

Back to the Pilliga The Call of the High Country

The Call of the High Country Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe

Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe