- Home

- Tony Parsons

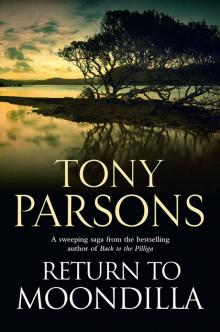

Return to Moondilla

Return to Moondilla Read online

Tony Parsons, OAM, is a bestselling writer of rural Australian novels. He is the author of The Call of the High Country, Return to the High Country, Valley of the White Gold, Silver in the Sun and Back to the Pilliga. Tony has worked as a sheep and wool classer, journalist, news editor, rural commentator, consultant to major agricultural companies and an award-winning breeder of animals and poultry. He also established ‘Karrawarra’, one of the top kelpie studs in Australia, and was awarded the Order of Australia Medal for his contribution to the propagation of the Australian kelpie. Tony lives with his wife near Toowoomba and maintains a keen interest in kelpie breeding.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Call of the High Country

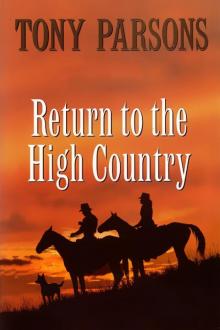

Return to the High Country

Valley of the White Gold

Silver in the Sun

The Bird Smugglers of Mountain View

Back to the Pilliga

NON-FICTION

Training the Working Kelpie

The Working Kelpie

The Australian Kelpie

Understanding Ostertagia Infections in Cattle

First published in 2015

Copyright © Tony Parsons 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Arena Books, an imprint of

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 76011 146 5

eISBN 978 1 74343 978 4

Internal design by Bookhouse

Typeset by Bookhouse, Sydney

Dedicated to my daughter Holly Lorraine Parsons, who tragically died in a car crash on 23rd August 2014.

Holly touched everyone who knew her.

She would have loved the Chief of this story.

Her two German Shepherds, Dougal and Wishes, were with her and both survived the crash.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE

CHAPTER FORTY

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

EPILOGUE

PROLOGUE

The white half-cabin launch rocked gently in the ocean’s swell, very close to the river’s mouth. There was a fitful north-easterly breeze. A breeze was always coming in off the ocean—only its direction changed.

Sam Corrigan and his son, Bevan, were fishing the run-in tide. They’d caught three flathead and hoped to catch a couple more before they pulled up anchor and headed back to shore. Some of Moondilla’s lights still glowed in the half-dawn, and away to the west the line of the Range was just coming into view.

‘Ready for a cuppa and a sandwich?’ Sam asked his son.

‘More than ready, Dad. I could eat a horse and chase the rider.’

Sam grinned. Bevan was eighteen, a champion swimmer, and his pride and joy. They had fished together just about from when Bevan could walk. He was ready to go off to university now, but he still never knocked back a fishing trip with his dad.

Father and son placed the rods in their holders and settled down to tea and roast-beef sandwiches. They were anchored on what passed as Moondilla’s bar, which was a minor thing compared with the bars of some rivers, making it a good place to rest. The water was so shallow that in a good light you could see the sandy bottom.

Sam reckoned that Moondilla was a particularly great fishing spot. There seemed no end to the types of fish you could catch around here. If you wanted real variety, you could go out to the Islands, a group of rocky islets a few miles off shore. On the other hand, if you didn’t fancy the big swell, you could fish fairly close in to shore, as Bevan and Sam were doing, or in the river itself. You’d always catch something for dinner.

When they’d had their fill and warmed their bellies, Bevan and Sam threw out with renewed expectation of more flathead. The run-in tide was now taking their lines away, so both men added a bit more lead to keep them from moving too far.

The tide brought all manner of sea creatures into the river, and they hadn’t been fishing again long when Bevan declared that he’d hooked something big. Sam looked at the bent rod and, with the wisdom of thirty years’ fishing experience, shook his head. ‘Naw, I think you’re hooked on the bottom.’

Bevan, who was using an expensive lure, admitted that his father was right. ‘But I’ll go down and see if I can rescue it,’ he said.

Sam wasn’t too happy about this proposal, given that there were sharks in these waters—but his son was a wonderful swimmer. Bevan handed the rod over to his father, took off his T-shirt and slipped into the water. Sam watched his body, still a bit worried, until it grew formless over the sandbank.

He didn’t have to wait long for his son to reappear.

‘Dad!’ Bevan burst out as he pulled himself onto the launch. ‘You won’t believe what’s down there.’ He had to catch his breath.

‘What is it?’

Bevan looked like he might be sick. ‘There’s a woman, a naked woman, and the lure’s hooked into her hair.’

Now Sam felt queasy. ‘I reckon you don’t have to say any more,’ he said. ‘Jesus, this is a nice kettle of fish. I never heard of anyone going missing.’

‘Well, there’s a woman down there and she’s not a mermaid, Dad.’

•

A few hours later, the divers got her up. She’d been secured with blocks of concrete so that she would never leave the bottom.

She appeared to be a young woman, although her face was badly disfigured. There was no jewellery, tattoos or distinguishing scars, which made her very difficult to identify. The other thing that puzzled the police was why she’d been dumped into relatively shallow water, but they reasoned that the river’s mouth was a secluded spot.

Moondilla’s medical examiner, Julie Rankin, conducted the

autopsy. She pointed to thin, very faint marks across the woman’s back, buttocks and thighs. ‘If I had to make a guess, I’d say that she’s been whipped with a fine leather strap. I found a tiny fraction of leather in her hair at the base of her neck.’

‘You think she was into kinky sex?’ Inspector Daniels asked, his eyebrow raised. He was the top cop in the district.

‘Either she was or the fellow who beat her was,’ Dr Rankin said, calm and composed. ‘But it was heroin that killed her.’

It seemed that no amount of police work could reveal the woman’s name.

And it was from around this time that Moondilla changed in character from a place of very little crime to the centre of drug activities on the South Coast. It began with the sea, and it was the sea and the river that made Moondilla.

CHAPTER ONE

The town of Moondilla was tucked neatly between two promontories that reached out into the vast Pacific Ocean like fat fingers. Within this horseshoe-shaped reach of coastal heath and ivory-hued beaches, there was a river that emptied into and was sustained by the ocean. Protected by the harbour, the river’s mouth didn’t have the usual bar and wasn’t as open to the sea as some other coastal rivers.

On the southern side of the delta, and forming part of the southern promontory, was a tiny beach. A bit farther up from the ocean, a bridge spanned the river, connecting Moondilla to the main highway that wound south towards Victoria.

On the northern or town side of the delta was a broad stretch of sand, usually referred to as Main Beach, and skirting this beach was a wide road that swung in a half-circle to join up with the highway north of Moondilla.

The town’s boundary was around two kilometres from its centre and, except for a few farmhouses, the countryside was quite scantily populated. Most people in the area, quite naturally, had clustered around the river and the ocean.

Close by the town was a long wharf or jetty that reached out into the harbour, and at which the fishing trawlers moored to unload their catches. A bitumen road led right up to the jetty so that vehicles could load up with seafood for various markets. There were a couple of smaller jetties southwards of this main one, and here many private launches and yachts were moored.

The road to Sydney provided the greatest number of visitors to Moondilla, but tourists came from everywhere, even from overseas, almost exclusively for the fishing. Even the famous western writer and big-game fisherman Zane Grey had fished this area of the coast, helping to give it an enduring popularity.

Moondilla was also widely regarded as a nice little town for a holiday, being relatively unspoiled by the kind of developments that had changed the character of other coastal towns. For most of its existence, it had had a very low crime rate—but startling new happenings were, to use a marine expression, rocking the boat, and giving the police, both state and federal, cause to put the town under closer scrutiny.

•

It was the most startling of these happenings that occupied Greg Baxter’s attention as he drove in to Moondilla. The body of a young woman had been found weighted with concrete blocks not far off the mouth of the river. This horrific discovery had been a boon for the South Coast media, but especially for the Moondilla Champion, which ran front-page feature stories for several days. Nothing like this had ever happened in the town and it was, needless to say, the main topic of conversation wherever people met.

It was clearly a case of murder, although the police hadn’t revealed any details of the post-mortem. This suggested to Baxter that there were sinister findings which they were reluctant to release to the public, even though they were being pressed to do so.

Baxter’s usual sharpness might have been slightly dulled by his preoccupation with the murdered woman, but his reflexes—finely honed by decades of gymnastics and martial arts training—took over when he saw the overturned four-wheel drive. He braked, pulled his car to the side of the road, jumped out and rushed over.

This was well known to be a bad section of road—although the surface was up to standard, the combination of its camber and curve were car killers. The four-wheel drive had hit a tree and flipped onto its side. Baxter peered in the driver’s window. Its passengers, a man and a woman, were both alive and semiconscious. Neither was capable of getting out, and both were covered in blood.

Baxter had to lean through the window to turn the ignition off—strong as he was, he couldn’t budge the door, which had been partly crushed. By now, a couple of other cars had pulled up, and a driver poked his head out, shouting, ‘Need any help?’

‘Ambulance,’ Baxter called back, ‘and have you got any tools on you?’

But none of them had—they were city people out for a jaunt, and they all looked frightened. Heart thumping, Baxter hurried back to his car and riffled through his toolbox for a ‘jemmy’. He doubted it was strong enough, but it was the only thing he had that might work.

After a ferocious effort that left his arm strangely numb, he’d just managed to get the driver’s door open when the local ambulance arrived with siren blaring, and two paramedics rushed over.

‘You’ve gashed your arm pretty bad there,’ said the older ambo. ‘Sit down and take it easy, and we’ll see about getting this pair out.’

Baxter glanced at his arm, surprised to see the blood dripping down. But, he reasoned, it could wait until they’d rescued the passengers.

CHAPTER TWO

Baxter, his arm wrapped in blood-soaked bandages, was waiting on a chair in the emergency section of Moondilla’s medical clinic. The wound didn’t trouble him too much—he’d had worse. He was thinking about Moondilla. He’d left the town as a small boy, and one of his strongest memories was of the lovely river that made Moondilla what it was. He’d spent hours watching his father fish off a jetty or from his small runabout.

Baxter hadn’t wanted to leave; he’d felt sure there would never be another place as good as Moondilla. But he was only a child and had no say in the matter. Moondilla was the place where his mother, Frances, had begun her culinary career, but she had outgrown it. They’d moved to Sydney, where she’d developed and sold one restaurant after the other, making a heap of money and becoming known to all and sundry as the Great Woman.

Baxter was still thinking about his mother, and how good she’d been to him, when Dr Julie Rankin came through the door.

‘My God! Greg Baxter! You’re the last man I expected to be treating,’ she said when she saw him, and gave him a big smile.

‘And it’s nice to see you too, Julie,’ Baxter said, grinning. She was a sight for sore eyes. They’d parted on very good terms just prior to her going to London for further study. She’d been exceptionally ambitious, with the clear-cut aim of becoming a top surgeon. He had never imagined that she’d come back to Moondilla.

Although they were both from the town, they’d first met in Sydney when Julie had signed up as one of Baxter’s martial arts students. She’d set out to reach his level, but he was so far ahead of her that, try as she might, she could never have been in his league. Of course, the fact that he’d been a gymnast of near-Olympic standard gave him an enormous advantage. But he had pushed her quite hard in judo, and she was brown-belt standard when she left him.

‘Sorry, Greg,’ Julie said, ‘I didn’t expect to find you here.’ She began unfolding his blood-soaked bandages. ‘What on earth are you doing in Moondilla?’

‘I live here, Julie,’ Baxter replied with a half-smile.

‘You live here? Where? And for how long?’

‘I bought the Carpenter place out on the river. You probably know it.’

Julie nodded, her brow furrowed. She was preoccupied with his bandages, but still seemed to be taking in his words, so Baxter kept talking.

‘How long have I been there? A few weeks. I’ve been pretty busy getting settled in. My mother insisted on me making a few changes to the house. To the kitchen, mainly. That and some glamming up of the main bedroom.’

‘Good heavens,’ Julie exclaimed.<

br />

Baxter couldn’t tell whether this remark was made in response to the mention of his bedroom, or because she’d laid bare the wound on his arm.

‘This is going to require quite a few stitches,’ she said, her eyes wide. ‘How on earth did it happen?’

‘Well, I reckon I couldn’t have anyone better to sew me up, could I?’ Baxter said and laughed. ‘The last time I saw you was just before you left for Pommyland to specialise in surgery, and knowing you I’d put my money on you doing just that.’

‘Greg, how did you come by this?’ she asked again, more urgently this time. ‘The message just said that there was a man who’d cut his arm rather badly in some sort of accident.’

Baxter shrugged and told her the story.

‘I suppose the car could’ve blown up?’ she asked, a stern note in her voice.

‘I turned the ignition off first thing, and I was just going to try and get them out when the ambos arrived—I reckon they took the passengers to Bega Hospital—and then the cops showed up. One of them gave me a lift here in my car.’ He sighed, thinking of the injured couple and their ruined vehicle, which he’d noticed was filled with holiday gear. ‘That’s a very bad curve and it needs straightening out. Beats me why it wasn’t done years ago.’

Then Baxter realised that Julie had gone very still. ‘My brother Andrew was killed on that curve,’ she said, her voice trembling slightly although her eyes were dry. ‘Andrew and a mate. They’d been to a birthday party. Andrew wasn’t driving, and his mate was high as a kite on drugs and took the curve too fast.’ She appeared to steel herself before she kept working on Baxter’s wound—but then she added, under her breath, ‘Andrew was in second-year medicine.’

Baxter knew her better than to try physical comfort, so he just said, ‘I’m so sorry to hear that, Julie.’

‘It nearly killed my mother. My brother was the apple of her eye.’

‘Not you?’ Baxter queried, sensing an opportunity to lighten the mood.

Julie rewarded his effort with a half-hearted smile. ‘No, not me. Mum and I didn’t get on very well in those days. She was jealous that I was so close to Dad. But it was just that she didn’t share any of his likes, whereas I did. I’d fish with him for hours at a time . . . Don’t move your arm while I give you some local anaesthetic. It will deaden the pain while I stitch up that cut.’

Long Gone the Corroboree

Long Gone the Corroboree #taken

#taken The Family Way

The Family Way One For My Baby

One For My Baby Man and Boy

Man and Boy The Murder Bag

The Murder Bag Return to Moondilla

Return to Moondilla Beyond the Bounty

Beyond the Bounty Die Last

Die Last The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe)

The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe) Stories We Could Tell

Stories We Could Tell Return to the High Country

Return to the High Country Silver in the Sun

Silver in the Sun My Favourite Wife

My Favourite Wife Dead Time

Dead Time Girl On Fire

Girl On Fire Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood

Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood Catching the Sun

Catching the Sun The Slaughter Man

The Slaughter Man Men from the Boys

Men from the Boys Man and Wife

Man and Wife Valley of the White Gold

Valley of the White Gold Back to the Pilliga

Back to the Pilliga The Call of the High Country

The Call of the High Country Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe

Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe