- Home

- Tony Parsons

The Call of the High Country

The Call of the High Country Read online

PENGUIN BOOKS

The Call of the High Country

A. D. (Tony) Parsons, OAM, has worked as a professional sheep and wool classer, an agricultural journalist, a news editor and rural commentator on radio, a consultant to major agricultural companies, and an award-winning stud breeder of animals and poultry. He owned his first kelpie dog in 1944, and in 1950 he established ‘Karrawarra’, one of the top kelpie studs in Australia. In 1992 he was awarded the Order of Australia Medal for his contribution to the propagation of the Australian kelpie sheepdog.

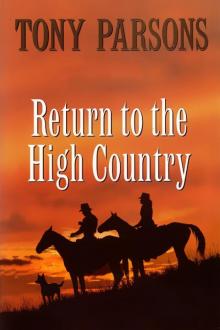

Since 1947 Tony has written hundreds of articles, many in international publications. His technical publications include Understanding Ostertagia Infections in Cattle, The Australian Kelpie, The Working Kelpie and Training the Working Kelpie, now regarded as classic works on the breed. His novels, The Call of the High Country, Return to the High Country, Valley of the White Gold and Silver in the Sun, are bestsellers.

Tony lives with his wife not far from Toowoomba in Queensland and successfully showed merino sheep and wool until 2005. He still maintains a stud of kelpies.

Praise for Tony Parsons’ bestsellers

‘Everything a good Australian novel should be – a bit of believable outback, a bit of local community angst, some intrigue, and past lives … keeps the reader guessing all the way through.’

NEWCASTLE HERALD

‘… heroism in adversity, romance and the good old Aussie bush, with an added dash of contemporary flavour. An armchair alternative to McLeod’s Daughters, with greater depth.’

BENDIGO ADVERTISER

‘This bestselling author delivers the goods again. Silver in the Sun will transport you to an outback Queensland sheep station where the river runs through the wide brown land and silver trees gleam in the sun. I couldn’t put it down.’

SOUTH COAST REGISTER

‘With each new book, Tony Parsons’ rural readership grows. It is easy to see why. Not only is the writing informed but it will have readers edgy with expectation.’

WEEKLY TIMES

‘Tony Parsons comes across as a very intelligent man hugely experienced in Australian country life, and an incurable romantic who likes happy endings. His many fans won’t be disappointed with this new offering.’

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN LIFE

‘Set in contemporary rural Australia, Parsons’ books combine an old-fashioned sensibility with a hard-nosed look at the reality of farming in Australia today.’

THE AGE

‘Anyone who is a fan of McLeod’s Daughters will love this novel. If you’ve ever wanted to experience life on an Australian sheep station, this book will take you there.’

SOUTH COAST REGISTER

‘A story of love and triumph against adversity that will transport you to the heartland of Australia’s high country and keep you spellbound until the very last page.’

LIVING MAGAZINE

‘A heart-warming saga of family tribulations, an intensely powerful and moving story with a true-blue Aussie flavour.’

COUNTRY NEWS

‘This book comes from the heart of country Australia in more ways than one. There is much to be said for listening to a genuine voice of rural Australia.’

COURIER MAIL

The Call of the High Country

Tony Parsons

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (Australia)

250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada)

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Canada ON M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL England

Penguin Ireland

25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd

11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ)

67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd

24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London, WC2R 0RL, England

First published by Penguin Books Australia Ltd 1999

Copyright © Anthony Parsons 1999

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

penguin.com.au

ISBN: 978-1-74-228377-7

To my mother, Evelyn Margaret Parsons, who was thrilled that this book was on the way, but who did not live to see its publication.

Author’s Note

It was once suggested to me by a visiting American friend that I should write a work of fiction in which the working kelpie played a prominent role. The suggestion stayed in my mind for several years; in fact, through all the years in which I was heavily engaged in writing three technical books on the working kelpie. I kept thinking back to my early years in the sheep and wool business when I had spent a lot of time in the Liverpool Range region of New South Wales. It was there that I met the sheepdog breeders and handlers and saw the dogs that would shape my future thinking on sheepdogs.

Nearly all of the great dog men who lived in the country at the head of Half Moon Creek and Jimmy’s Creek have gone. The incomparable Quirindi master, Frank Scanlon, has gone, and I doubt that we shall see his like again, or the likes of the dogs he and his contemporaries worked with in the high country of this story.

The she-oaks still sigh along Half Moon Creek but the great stations like Collaroy and Brindley Creek are miniscule in area compared with what they were in the early days.

There are no such places as Yellow Rock or Wallaby Rocks but there are places just like them. I know because I have ridden over them and I have watched the eagles soaring above the peaks.

David and Andrew MacLeod are composites of several men I came to know and call my friends, and Anne MacLeod is an amalgam of several dozen women who put up with me and fed me while their menfolk passed on the knowledge and information that I sought with such zeal. Even Sister Kate Gilmour had her counterpart in my travels.

In truth, this book is a blend of fact and fiction. There are names in it, surnames specifically, which are well-known in some country districts, but in no instance do such names represent any person, living or dead. Other things have been altered to suit the purposes of fiction, such as the size and procedures of the Merriwa Hospital.

A lot of Merriwa people were very kind to me in many ways. It is a long while since I rode a borrowed black mare up onto the tops, and saw for the first time the kind of country that Tom Bower and the Cronins worked their dogs over. I regret that it has taken me close to fifty years to do something worthwhile to acknowledge the kindnesses of these people.

And of course we should not forget the late Athol Butler, who worked the legendary Johnny and scored the possible 100 points at the National in 1952. I was there when they did it. A colour picture of Johnny hangs beside my work table as a reminder of that dog and the ge

nius who handled him. Perhaps we shall one day again see someone achieve what he did. It is something to think about and to dream about.

Prologue

High, high above the top country of the Liverpool Range a wedge-tailed eagle hung in suspended animation. It was so high in the sky that it was nothing more than a speck, lost from time to time in the white fleecy clouds that drifted across the range. The eagle’s nest was on Oxley’s Peak, but its wonderful soaring flight carried it way beyond the Peak and it was now directly above High Peaks, where, among the broken, lightning-riven rocks and the caves, rock wallabies and rabbits found sanctuary.

Sitting on his pony on Yellow Rock, the highest point of Andy and Anne MacLeod’s High Peaks property, David MacLeod watched the eagle and envied it. From up there in the sky, the eagle would be able to see all of High Peaks and much, much more. Some bushmen said that eagles were bad news because they killed lambs, though David had never seen this. To him the eagles were wild and free and they belonged to the high country, just as he felt he did. As always when he watched the flight of an eagle, his spirits lifted. He never tired of watching the great birds. He knew where all their nests were on High Peaks and the eagles’ secret places were safe with him.

David had never wanted to live anywhere other than High Peaks, except, perhaps, for the Whites’ place next door. It ran right to the top of the range, like their own property, but it also had a wonderful, grassy valley where Wilf White ran his brood mares and yearlings. In this valley lucerne grew so well that you could get several cuts a year without irrigation.

As David watched, the eagle dropped like a stone towards Wallaby Rocks on the Whites’ place. He lost sight of it momentarily and then it rose, clumsily, appearing with a rabbit hooked in its claws. Its huge wings propelled it upwards and then it banked, just like an aeroplane, and flew towards Oxley’s Peak. It crossed the creek, genesis of the Hunter River, and was lost to sight.

David knew he was going to be late home for lunch, but that was nothing new. He was always late when he rode off into the hills with a kelpie running beside his pony. The range country of High Peaks seemed to cast a spell over him; a spell so powerful he could not resist it. He was content to simply sit and gaze at the landscape around him, to watch the creatures and birds that inhabited it. At other times he put his pony to feats which, if his mother had known about them, would have brought grey hairs to her head and probably resulted in his confinement to the homestead area. There was no fun in riding down an established track; the real fun was making your own.

David MacLeod was not very old when he realised that he had a special feeling for High Peaks. He had heard his mother telling people that her son ‘loved’ High Peaks. He wasn’t sure he knew the meaning of the word love, but he did know that there could be no place else like High Peaks – and he was part of it. He didn’t like leaving the property for even half a day, so the times he spent away from it at school were almost intolerable. But at least he could see the range through the windows of his classroom. And at lunchtime he could sit and look at the peaks and remind himself that come the weekend he would be riding them.

What David really lived for was the day when he would be finished with school and could spend all his time at home. He didn’t need to know all the things they were trying to stuff into him. It wouldn’t make him a better stockman or judge of stock.

‘No, David, it won’t make you a better stockman, but it will make you a better man,’ his mother chided. ‘There are more things in life than properties and dogs and horses. The sooner you realise that fact, the better it will be for you. Besides, there is more to being a successful property owner than you imagine. Keeping a good set of books and records is also important. Even your father went to school,’ Anne reminded him.

‘Not for long,’ David replied.

‘That was a great pity. Your father is a very intelligent man and it was a real shame that circumstances forced him to leave school prematurely.’

‘Well, I want to be just like Dad. That’s good enough for me,’ David said with as much conviction as a ten-year-old boy could put into words.

There was another good reason why David MacLeod virtually haunted the high country – it gave him the chance to work one of his father’s kelpies. It was very difficult country to muster; so difficult that odd sheep missed out on getting mustered when they needed crutching, drenching and shearing. Crutching kept the britch end of the sheep free of stains and dags, but flies also struck sheep on the body, especially after rain in spring and autumn. Old hands told of fly seasons so bad that flies would strike sweaty saddlecloths and even crushed thistle leaves. A sheep struck by flies and left untreated will eventually lie down and die. So if you saw a struck sheep you first of all had to catch it, which was not always easy in the high country, and you then had to cut the wool away with dagging shears to expose the maggots. Fly dressing was applied to the affected area and the sheep was released. Catching and holding a big range wether was no easy task for David, although he was much stronger than most boys his age. He had done his share of axe work, helping out when his father was ‘ringing’ trees.

The trick in catching a wether was to try and work it into a blind gully. This was difficult to do if a sheep was on its own, but quite often the ‘rogue’ sheep ran in twos and threes. The first thing they would do when they sighted boy and horse was to bolt for the most inaccessible spot they could find. The job of winkling them out then had to be left to a hill-wise dog.

As David sat watching the eagle, he saw movement in the scrub below him. It was a very rough hill, covered with low scrub and odd kurrajong trees. He thought it was probably either a wallaby or a roo, but patient watching revealed it to be not one but three wethers. Two were crutched so would have been drenched at the home yards, but the third sheep had been neither crutched nor shorn. It had missed last shearing, which suggested that it could be a pea-eater. These were sheep that ate a weed called the Darling Pea and became quite mad, virtually impossible for a dog to handle. They didn’t survive very long. The problem was that in dry times the Pea was often the only green plant on the hills and some sheep wouldn’t leave it alone. On the other hand, the unshorn sheep might be a pure and simple rogue which had hidden in the scrub when mustering was in progress and could not be flushed out with whip cracks.

David considered the situation and resolved to try and take the sheep back to the shed. It was a long way to pull three sheep, but if he let the woolly one go, it would probably get struck and they would lose it. His father hated losing sheep.

It was lucky that he had old King with him. King was an old blue and tan kelpie his father had won a lot of trials with over the years, and he was considered to be one of the best and brainiest dogs Andy MacLeod had ever handled. David looked down at the dog and hissed, but he need not have worried – King had seen the wethers and was watching them intently.

‘Keep out, King,’ he said softly, so as not to disturb the sheep. He wanted King behind them before they realised there was a dog around.

King slipped away up the hill, knowing, from all his years of experience in the hills, that as soon as the sheep saw him they would bolt for the tops. That usually meant a lot more hard work to get them back.

David took up the reins of his pony and waited for King to make his lift. The two crutched wethers saw him first because they had been ‘wigged’ and had better vision than the woolly. They milled and were undecided what to do. David soon realised that the woolly wether was a rogue. Its first instinct was to bolt. King blocked it several times and turned it back to the other two wethers. It was then that David witnessed a wonderful piece of dog work. As King drove the sheep down the hill and away from the scrub, the rogue turned and jumped for the gully which ran right up to the tops. King leapt and snapped his teeth not six inches from the wether’s head. It crashed to the ground, got up, and meekly joined the other two.

David rode down the hill after King and the sheep and then took up point positio

n ahead of them. In this fashion he eventually brought the three sheep back to the home yards. There, the tall figure of his father was waiting for him.

‘Mum’s worried as hell about you, Davie. Can’t you ever get home on time for meals?’

‘Sorry, Dad. I found this unshorn wether and I reckoned the best thing I could do was bring him back. He’s a bit of a rogue and took some handling.’

‘Where did you find him?’ Andy asked.

‘The Whites’ side of Yellow Rock,’ David said.

‘That’s some trip. How did you keep them clear of the other sheep?’

‘It wasn’t easy. I had to make a few detours. That’s why it took so long. Did I do the right thing in bringing this woolly in?’

‘I reckon you did, but I don’t know how you managed it.’

David grinned. It really hadn’t been all that difficult. Not with King to do most of the work.

‘King did an amazing thing up at Yellow Rock. He’s still a beaut dog, Dad.’

Andy nodded. ‘He knows it all, Davie. Dogs get better with age. They know all the short-cuts and learn to outguess sheep. They get to know what sheep will do in certain paddocks. Now, you’d better scoot for the house. Tell your mother you’re sorry you’re late and explain what you did.’

Andy shook his head as his son ran off. He found it hard to believe that even David could have brought three wethers a distance of three miles, most of it rough country and grazed by a couple of thousand sheep. He had thought the boy was too young to work at the local sheepdog trial, but it was clear that he was wrong. He would have to let him have a go. The boy was a freak. He could be a pain in the arse the way he worried his mother, but he was a hell of a kid for all that. He reckoned he’d been damned lucky to have one like him. And damned lucky to get a wife like Anne, for that matter. She could have done a lot better for herself than marry him. Anne and David. Andy could do anything, face anything, with them to come home to.

Long Gone the Corroboree

Long Gone the Corroboree #taken

#taken The Family Way

The Family Way One For My Baby

One For My Baby Man and Boy

Man and Boy The Murder Bag

The Murder Bag Return to Moondilla

Return to Moondilla Beyond the Bounty

Beyond the Bounty Die Last

Die Last The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe)

The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe) Stories We Could Tell

Stories We Could Tell Return to the High Country

Return to the High Country Silver in the Sun

Silver in the Sun My Favourite Wife

My Favourite Wife Dead Time

Dead Time Girl On Fire

Girl On Fire Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood

Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood Catching the Sun

Catching the Sun The Slaughter Man

The Slaughter Man Men from the Boys

Men from the Boys Man and Wife

Man and Wife Valley of the White Gold

Valley of the White Gold Back to the Pilliga

Back to the Pilliga The Call of the High Country

The Call of the High Country Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe

Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe