- Home

- Tony Parsons

Back to the Pilliga

Back to the Pilliga Read online

Tony Parsons, OAM, is a bestselling writer of rural Australian novels. He is the author of The Call of the High Country, Return to the High Country, Valley of the White Gold and Silver in the Sun. Tony has worked as a sheep and wool classer, journalist, news editor, rural commentator, consultant to major agricultural companies and an award-winning breeder of animals and poultry. He also established ‘Karrawarra’, one of the top kelpie studs in Australia, and was awarded the Order of Australia Medal for his contribution to the propagation of the Australian kelpie. Tony lives with his wife near Toowoomba and maintains a keen interest in kelpie breeding.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Call of the High Country

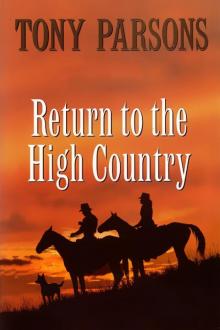

Return to the High Country

Valley of the White Gold

Silver in the Sun

The Bird Smugglers of Mountain View

NON-FICTION

Training the Working Kelpie

The Working Kelpie

The Australian Kelpie

The Kelpie

Understanding Ostertagia Infections in Cattle

TONY

PARSONS

Back to the Pilliga

First published in 2013

Copyright © Tony Parsons 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Arena Books, an imprint of

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 052 6

Set in 11/18 pt Sabon by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my father

the late Ronald David Parsons, BEM

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

EPILOGUE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

CHAPTER 1

There were four of us Sinclair children – three boys and a girl. Stuart was the oldest, my sister Flora came next, and I turned up just fifteen months after her. Our little brother, Kenneth, was the baby of the family.

Our father was a firm disciplinarian and never hesitated to give us a hiding if we failed to carry out our allotted tasks around the property, like feeding the horses, dogs and poultry. Flora and I copped our hidings in silence whereas at the first stroke of my father’s belt or switch, Stuart would scream so loudly it usually brought my mother to his rescue.

Dad had an exalted view of his place in the Kamilaroi district, and anything that reflected on his reputation as an arbiter of good taste was anathema to him. This sometimes resulted in severe punishment for us if we stepped out of line. Being a girl didn’t cut any ice with my father and he’d switch Flora with equal severity as us boys. Flora wasn’t in any sense a ‘bad’ child but she was a real tomboy and my father thought that some of the things she did weren’t ‘ladylike’.

One of the worst hidings I received, and Flora copped it too, was when Stuart snitched on us for skinny-dipping in the creek. This was considered reprehensible behaviour but what made it even worse was that our school friend Fiona Cameron, a tomboy of the same ilk as my sister, was skinny dipping with us. This really inflamed the situation because my father thought it reflected badly on him and the way we had been raised. Quite apart from the hidings for skinny-dipping, Flora and I were given additional tasks to do and received no pocket money for three months.

What made the punishment even more onerous was that we were given some of Stuart’s jobs in addition to our own while he kept on receiving his usual pocket money.

Although I was only a boy at the time that Stuart snitched on us, afterwards I harboured a residual dislike for him and I didn’t like working with him on any kind of task. This wasn’t because he was lazy or lacked interest in the activities associated with a big grazing property but because of his personality. He was continually trying to ingratiate himself with our father and it didn’t concern him how badly we appeared. He’d sometimes lie to Father that he’d had to do one of my jobs. In fact I rarely ever skipped a job and covered for Stuart on several occasions.

The first time I gave Stuart a bleeding nose was when he fibbed about riding his pony. Father had found it lame and told me to tell Stuart he wasn’t to ride it until the vet had looked at it. Stuart rode the pony and later told Father that I hadn’t given him the message.

‘You’re a liar as well as being a snitch,’ I told him before punching him in the face. ‘Don’t ever ask me to do anything for you again.’

I was punished for giving him the bleeding nose but it was worth it for the satisfaction it gave me. From that day on neither Flora nor me told Stuart any of our ‘secrets’ – like the time we set duck eggs under one of Father’s prize Australorp hens. He never did discover how that happened.

Stuart modelled himself on our father who, despite being respected for his ownership of Kamilaroi, was not well liked in the district.

As well as being one of the reasons for my dislike of Stuart, the day we went skinny-dipping was also the day I realised that girls were made differently to boys.

CHAPTER 2

When I was growing up on Kamilaroi it was the second largest property in the general Coonabarabran area and was as much a part of the district as the adjacent Pilliga Scrub.

The first rule on Kamilaroi was that my father’s word was law and couldn’t be disputed under any circumstances. As well as dominating his family, my father tried to dominate every organisation with which he became involved, including the old Pastures Protection Board and the local show society. Though not much loved, my father held a privileged position in the district because of his ownership of Kamilaroi. There were people who sucked up to Father to get his business, which sometimes worked and sometimes didn’t. But if a business got on the wrong side of him, that was the end of the relationship.

Father was a very much larger than life character. It wasn’t that he had a great sense of humour because he had very little of that commodity. The fact was that he had a great presence. He looked like an aristocrat and he behaved like one. He was about six feet in height with wide shoulders and a trim waist which didn’t thicken substantially until he was an old man. He had a face you could nev

er forget because of his brow and his keen grey eyes. He had the brow of an intellectual though he didn’t possess a brilliant mind. I’d say he was smart and he ran Kamilaroi like a well oiled machine. He cultivated a moustache which certainly suited him. He was a martinet and he would have been a tough man to serve under in the 2nd AIF.

He’d had to take over the management of Kamilaroi as a quite young man when his father died as the result of war injuries in France. I reckon my father could have outwalked any man I ever knew. He walked with a springy kind of stride that ate up the ground. He had a fearsome reputation and when he came into the shed at shearing time all levity ceased. Father would have a look at the wool in the bins and then he’d go outside and cast his eyes over the shorn sheep in each shearer’s pen. If there were sheep cut about or unevenly shorn he’d have a word with the shearing contractor and that shearer would be replaced. I only ever knew of one contractor who argued the point with Father and he lost the shed.

As a boy growing up on a large sheep, cattle and grain property, I belonged to what was probably the last generation of children whose grazier fathers had real ‘clout’. The wool boom of the fifties was only a memory and the influence of the bush expressed via the old Country Party (now the National Party) had been very considerably reduced. The old bush socio-economic way of life was still there but the edifice was crumbling. Low wool prices, the 1975 slump in prices for beef cattle, indifferent seasons and higher costs were having a catastrophic effect on the financial viability of farming. Some of the great pastoral companies saw the writing on the wall and sold their historic properties. But many well managed properties continued to do all right, including Kamilaroi. There was still a good demand for our stud sheep and bulls, and my father also raced a couple of thoroughbred horses.

I’ve got to say that if it hadn’t been for my mother and Flora my childhood would have been hard to take. Mum was a very sweet person with a great deal of love to give, which she showered unreservedly on us children. She was always there to greet us when we arrived home from school, and the period between getting home and having dinner was a very special one because Father was either out on the run or away at one of his many meetings so we had Mum to ourselves. After we’d finished our chores we’d sit around the kitchen table and eat Mum’s incomparable shortbread, gingerbread men and sometimes hot pancakes. Mum would always ask how school had been and whether we had any problems with things like maths because she always had.

Mum came from a wealthy grazing family and why she chose our father as her husband was always a mystery to me because I doubt very much that she ever loved him. I have great difficulty accepting that she would have been party to an arranged marriage even though girls of her class had been expected to make good marriages. After they married, women like my mother were supposed to run their big homes and have children. They certainly weren’t meant to be engaged in anything as plebeian as working in an outside job. Funny that because in only a few years the definition of a viable farmer would become a farmer who had a wife with a job!

It seemed to me that my mother was a very special kind of woman; she was different. It wasn’t until after I left Kamilaroi and inhabited the wider world beyond its boundaries that I realised what made Mum different. It was style. Mum endowed everything she did with style. It wasn’t laid on with a trowel but part of her overall captivating personality. She was lovely; a brunette with natural waves and hazel eyes. And she was tall, only a couple of inches shorter than my father. Her movements, whether seen in the kitchen or outside in the garden, were always graceful.

Tradesmen loved her and would do almost anything for her because she treated them as if they were knights of the realm. There was always a cup of tea and a scone or a piece of cake for every tradesman who came to Kamilaroi. It infuriated my father but his sternest words had no effect on my mother who carried on as if she hadn’t heard him. I never heard a bad word said about her and her charm and natural warmth did a lot to offset my father’s standoffish image. My father might have been a pastoral patrician but my mother was a princess.

I wasn’t very old when I recognised that my father didn’t have much time for women generally. He behaved as if they’d been created to become wives and mothers and not to intrude beyond those areas. He told me once that women had innate problems and couldn’t be considered on the same plane as men. He never departed from this view; in fact he became even more intractable about it as he got older. This was very strange given that he’d married such a smart, capable and caring woman as my mother.

Though not as dismissive of women as Father, my brother Stuart had a high-handed manner with women which often rubbed them up the wrong way. Although he’d tried to model himself on Father, he was but a pale imitation of him, not possessing his aura or physical presence. Stuart was just below medium height and although not bad looking, he was not a man you’d look at twice unless he was on a horse. He had a lovely seat on a horse and it was something to see him and my father riding together. I wasn’t in their class as a horseman though I loved horses.

Stuart’s big problem was that he spoke down to everyone. Because he was up himself, he became the butt of jokes. I tried to ignore him as much as possible though this wasn’t always possible because we often had to work together in the sheep and cattle yards. Stuart wasn’t a great one for the girls because he spent most of his time trying to please Father.

I took the opposite direction – there was never a time when I didn’t like girls. From the first, I was very close to Flora, who was a ripper of a sister and was to remain my best friend all my life. Luke Stirling was my best mate but Flora was my best friend and there is a difference. Flora wouldn’t hesitate to chip me if she thought I needed it but I knew she did it for my own good.

Because of the location of Kamilaroi (it was named for the great Aboriginal tribe that once occupied a large area of northern New South Wales) we kids grew up with a fair knowledge of the unique character of the area around us, which included the vast Pilliga Scrub. You couldn’t drive in any direction from our property without traversing the scrub or land that had been cleared of scrub. The Pilliga had been the source of limitless tonnes of cypress pine and ironbark for both timber millers and landowners like my father. Virtually every stick of timber used on Kamilaroi was sourced from it.

For a kid like me, the Pilliga Scrub was much more than a never-failing source of timber, however: it was a place of mystery and challenge. Some of my very earliest memories are of listening to stories of strange happenings in the Pilliga Scrub. It was said that black panthers roamed there and numerous bodies were buried there. But by far the most stories were about stolen livestock being taken to the scrub, some for re-sale or simply to be butchered. So the Pilliga Scrub held a kind of awed fascination for me.

Soon after I gained my driver’s licence I began to explore the roads and timber tracks in the Pilliga Scrub, often following the route taken by Jimmy and Joe Governor during their violent rampage – which included nine murders and the rape of a fifteen-year-old girl. Sometimes referred to as the Breelong Blacks, the Governors were actually half caste and used rifles, shotguns, tomahawks and nulla nullas in their crimes. They were eventually tracked by bloodhounds and expert black trackers from Fraser Island before Joe was shot and killed north of Singleton by a man called John Wilkinson. Jimmy was shot in the Wingham area and then taken by steamer to Sydney where he was hanged at Darlinghurst gaol.

Once, as I was driving up a bush track in the Pilliga, a man stepped out of the scrub holding a rifle, which he pointed at me before telling me to scram. Heart thumping, I backed the ute up as fast as I could until I found a place where I could turn around and then hightailed it out of there. When I told Father about the man with the rifle he said he’d report it to the police though they would have Buckley’s chance of locating a lone man in a million acres of scrub.

Even without all the stories, the Pilliga Scrub could be a spooky place to be in at night. It was probably the thic

kness of the pines and their blackness when the sun went down that made it appear so eerie. With nightfall in the scrub came the orchestra of the pines and the sounds of crickets singing in the mulch, along with the coughing of koalas and the monotonous crying of mopokes. For anyone not raised in the bush or lacking exposure to noises of the night, the Pilliga could be a frightening experience. Later, years later, I discovered that scientists had proven that Aboriginal occupancy of the area could be traced back 21,000 years.

It was always understood that my father expected Stuart, Kenneth and I to return to Kamilaroi after we finished school. My father intended to expand our landholdings by buying at least one neighbouring property, his view being that you could never own too much land and that in Australia most holdings were too small to be really viable.

Kenneth turned out to be very bright and his school results were so good that my mother suggested he go on to university and study veterinary science, since he’d always been good with animals. Initially there was a great argument between my parents about the merits of Kenneth going to university, mainly because Mum had suggested it. Later, Father acknowledged that there’d be definite advantages to having a vet in the family. As well as helping generally with our livestock, Kenneth might be able to help set up and run the artificial breeding programs my father wanted to introduce. Despite his many personal faults, my father was a superb manager and he kept on top of all the latest developments in farming.

Unlike Stuart, I had mixed feelings about returning to Kamilaroi after boarding school. I liked the land well enough but the thought of working cheek by jowl with my father and Stuart didn’t appeal greatly. After the comparative ‘freedom’ of boarding school, it would be hard to endure my father’s bullying ways and the constant tension in the air that resulted from him being such a tyrant. Also, as I’d grown older, whenever I came home on holidays I hated the way he spoke to Mum on the rare occasions she opposed him. He never accepted that she knew anything about the property or what might be best for us.

Long Gone the Corroboree

Long Gone the Corroboree #taken

#taken The Family Way

The Family Way One For My Baby

One For My Baby Man and Boy

Man and Boy The Murder Bag

The Murder Bag Return to Moondilla

Return to Moondilla Beyond the Bounty

Beyond the Bounty Die Last

Die Last The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe)

The Hanging Club (DC Max Wolfe) Stories We Could Tell

Stories We Could Tell Return to the High Country

Return to the High Country Silver in the Sun

Silver in the Sun My Favourite Wife

My Favourite Wife Dead Time

Dead Time Girl On Fire

Girl On Fire Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood

Max Wolfe 02.5 - Fresh Blood Catching the Sun

Catching the Sun The Slaughter Man

The Slaughter Man Men from the Boys

Men from the Boys Man and Wife

Man and Wife Valley of the White Gold

Valley of the White Gold Back to the Pilliga

Back to the Pilliga The Call of the High Country

The Call of the High Country Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe

Girl On Fire_DC Max Wolfe